Introduction

Structured Secure Streams provide secure encrypted and authenticated data connection between endpoints. It's a simple userspace library written in c++14 and boost. It uses standard UDP to provide reliable delivery, multiple streams, quick connection setup, end-to-end connection encryption and authentication.

SSS is based on experimental, unfinished project under UIA - SST.

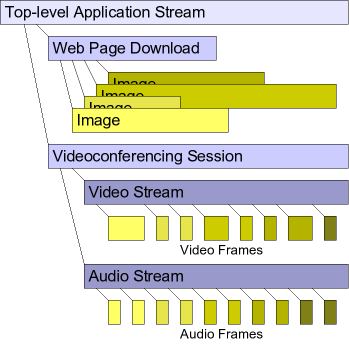

SSS is an experimental transport protocol designed to address the needs of modern applications that need to juggle many asynchronous communication activities in parallel, such as downloading different parts of a web page simultaneously and playing multiple audio and video streams at once.

Features of SSS

- Multiplexes many application streams onto one network connection

- Gives streams hereditary structure: applications can spawn lightweight streams from existing ones

- Efficient: no 3-way handshake on startup or TIME-WAIT on close

- Supports request/response transactions without serializing onto one stream

- General out-of-band signaling: control requests already in progress

- Both reliable and best-effort delivery in a semantically unified model

- supports messages/datagrams of any size: no need to limit size of video frames, RPC responses, etc.

- Dynamic prioritization of application's streams

- e.g., load visible parts of a web page first, change priorities when user scrolls

- End-to-end cryptographic security comparable to SSL

- Peer-to-peer communication across NATs via hole punching

Possible use cases

- Transfer files,

- Send audio/video streams,

- Implement secure RDP or shell services,

- Anything your application needs.

Advantages over TCP

- No head-of-line stalls if some packets are lost and need retransmission.

- No TIME-WAIT state before closing the stream.

- Quick connection setup - application can start sending data after 1 roundtrip.

- Mandatory encryption.

Advantages over plain UDP

- Reliable delivery supported.

- Large datagrams supported (both reliable and non-reliable delivery).

- Mandatory encryption.

The streams basics

The library is still in development, expect some interfaces to change. Refer to the generated Doxygen documentation for the actual up-to-date API calls list.

Constructing a host

Host represents an endpoint with its own public/private key pair, unique ID and a set of services.

First off, create a host instance.

auto settings = ;

// host_ptr_t is an alias for shared_ptr<host>,

// similarly for other classes

host_ptr_t ;

settings contain the generated host private and public keys (consult settings_provider API for more options).

Creating outgoing connection

To create an outgoing connection, create a stream instance.

auto stream = make_shared<sss::stream>;

stream->;

You need three pieces of information here.

- eid

- "service name"

- "protocol name"

A service name represents an abstract service being provided: e.g., "Web", "File", "E-mail", etc. A protocol name represents a concrete application protocol to be used for communication with an abstract service: e.g., "HTTP 1.0" or "HTTP 1.1" for communication with a "Web" service; "FTP", "NFS v4", or "CIFS" for communication with a "File" service; "SMTP", "POP3", or "IMAP4" for communication with an "E-mail" service.

Service names are intended to be suitable for non-technical users to see, in a service manager or firewall configuration utility for example, while protocol names are primarily intended for application developers.

A server can support multiple distinct protocols on one logical service, for backward compatibility or functional modularity reasons for example, by registering to listen on multiple (service, protocol) name pairs.

For example your Web server may register both ("Web", "HTTP 1.0") and ("Web", "HTTP 1.1").

"eid" is a self-certifying endpoint identifier, derived from the hosts's private key and independent of actual IP address. The previous article described some ways to associate EIDs with IP addresses and this is the task for routing module.

Routing module will be fully integrated with libsss later, at the moment you will need to manually create routing subsystems you need.

uia::routing::internal::regserver_client ;

uia::routing::client_profile client;

client.;

client.;

client.;

client.;

client.;

client.;

regclient.;

regclient.;

// Connect to as many regservers as you need

From the rendezvous server (in this case a local 192.168.1.67 machine) you can query other endpoints EIDs or query the current peer IP addresses based on EIDs you know.

EIDs are represented by instances of the peer_id class.

peer_id ;

This funny looking string is a base32 encoding of an RSA key fingerprint of some node. This one is fake so don't try to connect to it, anyway.

You'll also need to connect some signals from the stream to be aware of what's happening, we'll discuss it below.

Handling incoming connections

To handle incoming connections you need to create a server instance and make it listen on the specific (server, protocol) name pair.

auto server = make_shared<sss::server>;

server->on_new_connection.;

bool listening = server->;

;

If listening is true you have registered listener successfully.

You need to connect on_new_connection signal in order to handle connection events.

The canonical handler for the new incoming connection is as follows.

void

You need to iterate through all incoming streams, accepting them until accept() returns nullptr.

connect_stream_and_start_communication() function will need to connect some stream signals and perhaps start reading or writing data, or maybe just inform other application levels that it's time to do so.

Stream signals

Current stream API provides the following signals.

void ;

This signal is emitted when some bytes have been received and are now available for consumption.

void ;

This signal is emitted when a record marker arrives in the incoming byte stream ready to be read. This signal indicates that a complete record may be read at once.

void ;

This signal is emitted when a queued incoming substream may be read as a datagram. This occurs once the substream's entire data content arrives and the remote peer closes its end while the substream is queued, so that the entire content may be read at once via read_datagram().

void ;

This signal is emitted when our transmit buffer contains only in-flight data and we could transmit more immediately if the app supplies more.

void ;

This signal is emitted when some data from the transmit buffer has been sent and acknowledged, so the buffer space is now freed.

void ;

This signal is emitted when incoming data has filled our receive window. When this situation occurs, the client must read some queued data or increase the maximum receive window before SSS will accept further incoming data from the peer.

void ;

void ;

void ;

These three signals are emitted when apparent stream's connectivity changes. Up signal is emitted when the stream establishes live connectivity upon first connecting, or after being down or stalled. The on_link_stalled() signal is emitted at the first sign of trouble: this provides an early warning that the link may have failed, but it may also just represent an ephemeral network glitch. The application may wish to use this signal to indicate the network status to the user. Down signal is emitted when link connectivity for the stream has been lost. SSS may emit this signal either due to a timeout or due to detection of a link- or network-level "hard" failure. The link may come back up sometime later, however, in which case SSS emits on_link_up() and stream connectivity resumes.

If the application desires TCP-like behavior where a connection timeout causes permanent stream failure, the application may simply destroy the stream upon receiving the on_link_down() signal. Destroying a stream returns all undelivered packets to sender, so that it may attempt to establish a different stream to the peer, possibly at a different endpoint and resume communication.

void ;

Streams may create substreams at will. This signal is emitted when we receive an incoming substream while listening. In response the client should call accept_substream() in a loop to accept all queued incoming substreams, until accept_substream() returns nullptr.

void ;

This signal is emitted when an error condition is detected on the stream. Link stalls or failures are not considered error conditions.

void ;

This signal is emitted when the stream is reset by either endpoint. This may happen due to several different reasons. An application may call reset forcefully to shutdown the stream quickly. The stream may have read end of stream marker. A mismatch in stream identifiers or repeated packet authentication failure may have caused stream layer to send a reset packet.

Reading and writing bytes

ssize_t ;

byte_array ;

Read available data into the provided buffer up to max_size bytes in size. Or return all available data in a newly allocated byte_array, also not exceeding the requested max_size.

bool ;

Returns true if all data has been read from the stream and the remote host has closed its end: no more data will ever be available for reading on this stream.

ssize_t ;

Write data bytes to a stream. If not all the supplied data can be transmitted immediately, it is queued locally until ready to transmit. Returns the number of bytes written (same as the size parameter), or -1 if an error occurred.

Reading and writing records

int ;

bool ;

Return number of complete records currently available for reading. Second function returns true if at least one complete record is currently available for reading.

ssize_t ;

Return size of the first available record.

ssize_t ;

byte_array ;

Read a complete record all at once. Reads up to the next record marker (or end of stream). If no record marker has arrived yet, just returns without reading anything. If the next record to be read is larger than max_size, this method simply discards the record data beyond max_size. Returns zero if there is no error condition but no complete record is available for reading. Second function returns empty byte_array if an error occurred or there are no records to receive.

ssize_t ;

ssize_t ;

Writes the data in the supplied buffer followed by a record/record marker. If some data has already been written via write_data(), then that data logically forms the "head" of the record and the data presented to write_record() forms the "tail". Thus, a large record can be written incrementally by calling write_data() any number of times followed by a call to write_record() to finish the record. A record marker is written at the current position even if this method is called with no data (size = 0).

Reading and writing datagrams

ssize_t ;

byte_array ;

Read a datagram.

ssize_t ;

ssize_t Write a datagram. is_reliable flag indicates if datagram should be delivered as a reliable substream. Not reliable datagrams are akin to UDP packets, they are best-effort delivered with no guarantees made.

bool ;

ssize_t ;

Check for pending datagrams.

Working with substreams

SSS provides a cheap easy way to create substreams, adjust their priority and transfer data in many substreams in parallel.

stream_ptr_t ;

Initiate a new substream as a child of this stream. This method completes without synchronizing with the remote host, and the client application can use the new substream immediately to send data to the remote host via the new substream. If the remote host is not yet ready to accept the new substream, SSS queues the new substream and any data written to it locally until the remote host is ready to accept the new substream. Returns a stream object representing the new substream.

void ;

Listen for incoming substreams on this stream.

stream_ptr_t ;

Accept a waiting incoming substream.

Returns nullptr if no incoming substreams are waiting.

Other stream control functions

You can also set stream priority in relation to other substreams, change receive buffer sizes, get endpoint addresses of local and remote stream peer, give additional endpoint addresses for failover connections and more.

Examples

A working example of datagram streams with non-reliable delivery is available in the uvvy/voicebox library.

Building libsss

You'd need clang-3.4, libc++ and boost 1.54 or later built with libc++ support. Take a look at Travis-CI build script to see what needs to be done.

मेता